Component A

Organization and Culture

This chapter provides assistance to transportation agencies with the Organization and Culture component of Transportation Performance Management (TPM). It discusses where organization and culture occurs within the TPM Framework, describes how it interrelates with the other nine components, presents definitions for associated terminology, provides links to regulatory resources, and includes an action plan exercise. Key implementation steps are the focus on the chapter. Guidebook users should take the TPM Capability Maturity Self-Assessment as a starting point for enhancing TPM activities. It is important to note that federal regulations for performance-based programming may differ from what is included in this chapter.

Organization and Culture refers to the institutionalization of a transportation performance management culture within the organization, as evidenced by leadership support, employee buy-in, and embedded organizational structures and processes that support transportation performance management.

Introduction to Organization and Culture

For transportation performance management (TPM) to take hold within an agency, the organization and culture must be supportive. Changes to an established organizational structure and processes can be difficult for staff to accept. But when managed properly, the reward for an agency can be substantial. If the instituted changes are able to provide benefit to a broader group within the organization, the new way of conducting business will gain employee buy-in.

Transportation performance management can become a core agency activity when assimilated thoughtfully among staff, and adoption of TPM principles can contribute to improved results for the agency, system users, external partners, and funders. The discipline of adapting individuals within an organization to a different business culture and new business processes is often called change management.1 Change management is practiced today in different ways by different transportation agencies, but the key principles remain the same and provide several benefits.

Benefits include:

- Staff work as a cohesive unit rather than within silos

- Leadership can better justify activities from a data-driven perspective

- Policymakers see the agency as responsible, transparent, and accountable

- Employees discover efficiencies that reduce overall workload and expense

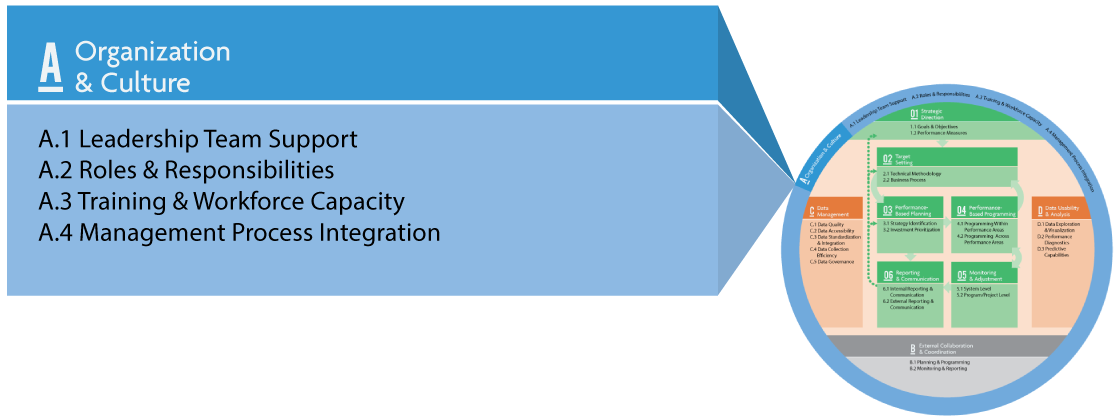

Note how the Organization and Culture component is depicted in the TPM Framework; it encompasses each of the other nine components because it impacts each component. Building a TPM culture is critical to the sustainability of processes established in other components. Without a supportive culture that has embedded structures and processes for TPM, newly implemented activities may fall by the wayside after only one or two performance cycles. This chapter provides implementation steps that, using a change management approach, will help an agency adjust its own structure and culture to better support TPM.

This change in structure and culture often occurs amidst a shift in other organizational priorities. Managing by performance results is rarely as simple as quantifying organizational and individual performance within existing goals. Rather, it frequently entails an affirmation–if not a complete reassessment–of agency vision and mission. Whether driven by a change in agency administration or by new legislation that prescribes performance metrics, leadership must not only align staff performance expectations with its management philosophies, but it should also foster an environment where change is embraced.

“We are focused on having an organization made up of people who are motivated and responsible for improving their work, while humble and helpful to those around them.”

Source: Kerry Benson, Utah Transit Authority

Component 01 of this guidebook details the importance of developing strategic goals for the organization that serve as the overall guiding force for agency decisions. All TPM activities tie back to agency goals, and staff should be focused on these goals as much as possible. Agencies often craft vision and mission statements before developing goals. A vision statement concisely and broadly describes desired outcomes and provides a basis for developing goals that more specifically spell out what the agency wants to achieve. Vision statements should serve as rallying points for staff. Mission statements reflect the core functional purpose of the agency. The Federal Highway Administration’s vision and mission are listed below as examples:2

- Vision: Our agency and our transportation system are the best in the world

- Mission: To improve mobility on our Nation’s highways through national leadership, innovation and program delivery

As discussed above, pairing TPM with change management becomes critical to TPM implementation. A successful pairing involves elements of both performance and change management philosophies.

Two examples of performance management philosophies include:

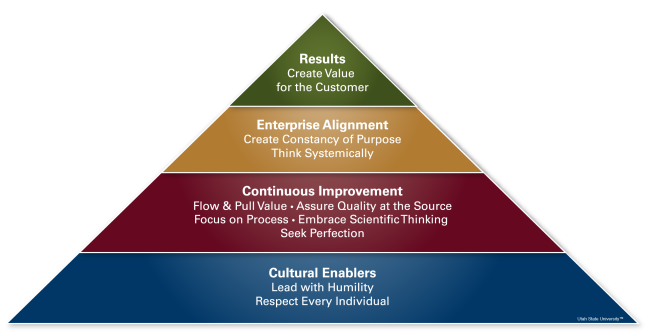

- The Shingo Model: This model, as illustrated in Figure A-1 below, is depicted as a pyramid with four levels, the foundation of which is Cultural Enablers such as “Lead with humility” and “Respect every individual,” and ascending levels being Continuous Improvement, Enterprise Alignment, and Results.3

Figure A-1: Shingo Pyramid Model

Source: Shingo Institute4

- Model of High Performing Organizations: Created by the Center for Innovative Cultures at Westminster College and includes elements such as “Distribute and use existing knowledge and new learning throughout the organization,” “Walk the talk, especially leaders,” and “Offer a strategic narrative that allows all organizational members to understand the impact of their contributions.”5

The Center points out that the vast majority of the American workforce is not actively engaged in its work, and therefore unable to reach their full potential. Citing a Gallup poll that estimates the cost to American corporations of “active disengagement” at $450 to $550 billion annually, the Center suggests that “the complexity and speed of change that organizations now face is stressing their capacity to adapt.” It suggests that performance can be improved and strategic competitive advantage achieved by strengthening an organization’s ability to change and adapt.6

The ability to adapt to a performance-driven culture should not be underestimated. Quantifying organizational performance can represent a new way of thinking. Applying metrics to individual performance can feel threatening, as if challenging staff to justify their position within the organization. A change management approach helps employees better understand the purpose of changes in their job roles, processes, and even use of technology.

- The ADKAR model was developed by Prosci to represent five levels an individual must achieve for change management to be successful:7

- Awareness. Employees must recognize the business reasons for change. Awareness occurs as the result of early communications related to an organizational change and helps individuals understand the impact change will have on them.

- Desire. Once an employee recognizes the business reasons for change, it falls to leadership to help cultivate desire and ownership of change among key staff. By managing resistance to change through active listening and sincere appreciation for staff concerns, leaders can better encourage engagement and participation by employees in the change process.

- Knowledge. The first two levels established a readiness for and acceptance of change. Knowledge teaches the individual how to change. It is the outcome of training and coaching and enables employees to realize or implement the change themselves at the required performance level.

- Ability. The ability of a single individual or of a team to effect change in an organization is nurtured through coaching, practice, and patience. Knowing how to change is important, but learning how to drive change is essential.

- Reinforcement. The ability of a single individual or of a team to effect change in an organization is nurtured through coaching, practice, and patience. Knowing how to change is important, but learning how to drive change is essential.

- Colorado DOT leveraged Prosci’s ADKAR and other change management practices in creating a Change Agent Network (Figure A-2) within the DOT. Individuals throughout the DOT, all with existing operational responsibilities, fill three key roles within the Change Agent Network:

- Change Agents. These individuals are located strategically throughout the organization to geographically represent a group of CDOT staff. Headquarters frequently deployed two change agents while each of CDOT’s five engineering regions hosted at least one.

- Change Leaders. Change leads are usually assigned for a specific, large change initiative and help ensure open and frequent communication about the initiative through the change agents and thus to a broader audience. Members of the project team usually feel invested in the change, but a far greater number of staff would be impacted by the change without directly influencing it. Change leaders, therefore, are tasked with collaborating with change agents to develop newsletters, web pages, and other communication devices for the benefit of the entire organization.

- Sponsors. Supervisors and senior executives who oversee project managers or champions of change initiatives are called upon as sponsors to assign change priorities, allocate resources to support those priorities, and keep change moving forward. Their purpose is not to enforce change but rather to foster an environment that readily accepts it.

Figure A-2: Colorado DOT Modified ADKAR Model

Source: Climbing the Mountain to Success8

Subcomponents and Implementation Steps

Figure A-3: Subcomponents for Organization and Culture

Source: Federal Highway Administration

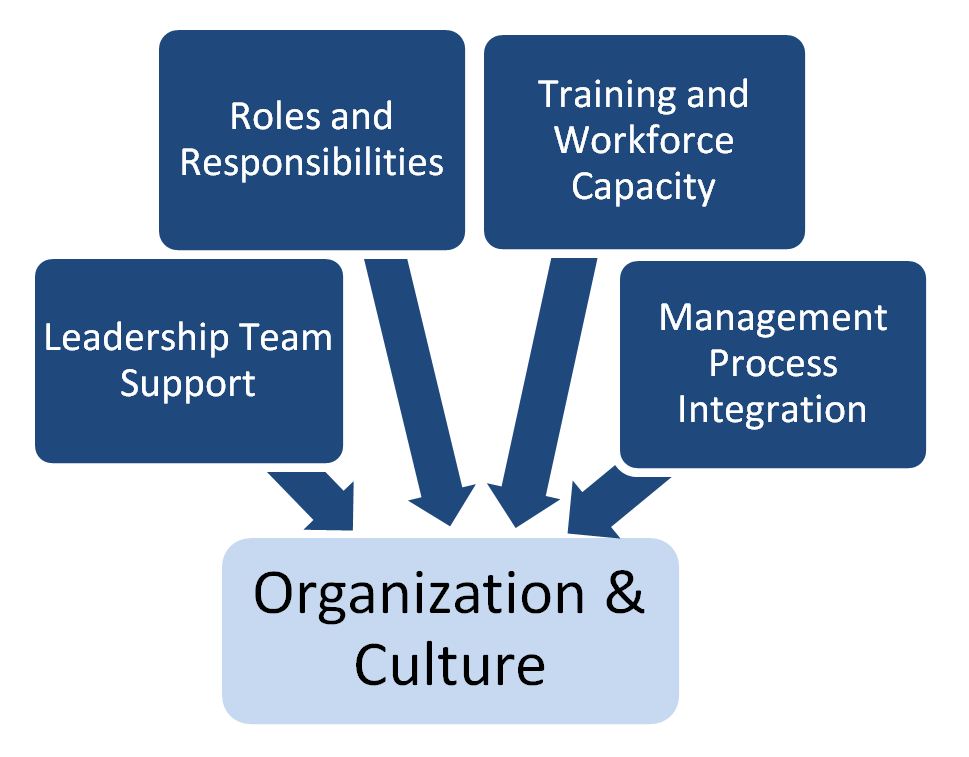

The successful pairing of TPM with change management obviously requires more than a revision to the organizational chart or a refining of employee job descriptions. To truly drive performance in an organization, the agency must understand how to prioritize its goals and how to manage any constraints that might prevent it from achieving them. The Organization and Culture component is broken down into four subcomponents as illustrated in Figure A-3:

- Leadership Team Support: Demonstrated support by senior management and executive leadership for transportation performance management.

- Roles and Responsibilities: Clearly designated and resourced positions to support transportation performance management activities. Employees are held accountable for performance results.

- Training and Workforce Capacity: Implementation of activities that build workforce capabilities required for transportation performance management.

- Management Process Integration: Integration of performance data with management processes as the basis of accountability for performance results.

Implementation steps, listed in Table A-1, for each of the subcomponents will help an agency create a transportation performance management culture by 1) building support among leaders by making the case for why transportation performance management is important, 2) assessing changes needed in the agency’s organizational structure and positions, 3) identifying and closing gaps in employee skills required for transportation performance management success, and 4) linking employee activities to strategic goals and objectives to improve performance results.

Source: Federal Highway Administration

| Leadership Team Support | Roles and Responsibilities | Training and Workforce Capacity | Management Process Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Evaluate how new agency processes have been implemented previously | 1. Assess current organizational structure | 1. Identify gaps in employee skillsets | 1. Incorporate performance discussions into regular management meetings |

| 2. Develop TPM pitch | 2. Develop scenarios to evaluate strategies | 2. Design, conduct, and refine training program | 2. Link employee actions to strategic direction |

| 3. Clarify role of senior and executive management | 3. Identify and implement changes to organizational structure | 3. Build agency-wide support for TPM | 3. Regularly set expectations for employees through measures and targets |

Clarifying Terminology

Table A-2 presents the definitions for the organization and culture terms used in this Guidebook. A full list of common TPM terminology and definitions is included in Appendix C: Glossary.

Source: Federal Highway Administration

| Common Terms | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Activity | Refers to actions taken by transportation agencies, such as projects, related to strategy implementation. | Paving key locations, adding new guardrail, rehabilitating a bridge, purchasing new buses. |

| Change Management9 | The discipline that guides how we prepare, equip and support individuals to successfully adopt change in order to drive organizational success and outcomes. | Individual change management requires understanding how people experience change and what they need to change successfully. Organizational change management provides steps and actions to take at the project level to support the hundreds or thousands of individuals who are impacted by a project. Enterprise change management is an organizational core competency that provides competitive differentiation and the ability to effectively adapt to the ever-changing world. |

| Goal | A broad statement of a desired end conditions or outcome; a unique piece of the agency’s vision. | A safe transportation system. |

| Mission | Statement that reflects the core functional purpose of an agency. | Plan, build, operate, and maintain a safe, accessible, efficient, and reliable multimodal transportation system that connects people to destinations and markets throughout the state, regionally, and around the world.10 |

| Objective | A specific, measurable statement that supports achievement of a goal. | Reduce the number of motor vehicle fatalities. |

| Outcome | Results or impacts of a particular activity that are of most interest to system users. Focus of subcomponent 5.1 System Level Monitoring and Adjustment. | Transit travel time reliability, fatality rate, percent of assets within useful life. |

| Output | Quantity of activity delivered through a project or program. Focus of subcomponent 5.2 Program/Project Level Monitoring and Adjustment. | Miles of pavement repaved, miles of new guardrail put into place, the number of bridges rehabilitated, the number of new buses purchased. |

| Performance Measure | Performances measures are based on a metric that is used to track progress toward goals, objectives, and achievement of established targets. They should be manageable, sustainable, and based on collaboration with partners. Measures provide an effective basis for evaluating strategies for performance improvement. | Transit passenger trips per revenue hour. |

| Target | Level of performance that is desired to be achieved within a specific time frame. | Two % reduction in the fatality rate in the next calendar year. |

| Transportation Performance Management | A strategic approach that uses system information to make investment and policy decisions to achieve performance goals. | Determining what results are to be pursued and using information from past performance levels and forecasted conditions to guide investments. |

| Vision Statement | An overarching statement of desired outcomes that is concisely written, but broad in scope; a vision statement is intended to be compelling and inspiring. | Minnesota’s multimodal transportation system maximizes the health of people, the environment, and our economy.11 |

Relationship to TPM Components

The ten TPM components are interconnected and often interdependent. Table A-3 summarizes how each of the nine other components relate to the organization and culture component.

Source: Federal Highway Administration

| Component | Summary Definition | Relationship to Performance-Based Planning |

|---|---|---|

| 01. Strategic Direction | The establishment of an agency’s focus through well-defined goals/objectives and a set of aligned performance measures | The strategic direction drives employee activities by defining agency priorities that should be focused upon in day-to-day work. |

| 02. Target Setting | The use of baseline data, information on possible strategies, resource constraints and forecasting tools to collaboratively set targets. | Agency targets define success for the agency, and lay the foundation for setting work group and individual employee targets. |

| 03. Performance-Based Planning | Use of a strategic direction to drive development and documentation of agency strategies and priorities in the long-range transportation plan and other plans. | A shift in organizational structure, workforce training, and change management at the agency enable performance-based planning processes to be completed sustainably. |

| 04. Performance-Based Programming | Allocation of resources to projects to achieve strategic goals, objectives and performance targets. Clear linkages established between investments made and their expected performance outputs and outcomes. | A shift in agency culture allows performance-based processes to be integrated into existing programming activities; the elements of the organization and culture component support this integration. |

| 05. Monitoring and Adjustment | Processes to monitor and assess actions taken and outcomes achieved. Establishes a feedback loop to adjust programming, planning, and benchmarking/target setting decisions. Provides key insight into the efficacy of investments. | Because this component is newly called out by the TPM framework, skill development and training related to Monitoring and Adjustment will be especially important. |

| 06. Reporting and Communication | Products, techniques, and processes to communicate performance information to different audiences for maximum impact. | This component promotes skill development and leadership support for improved performance reporting. |

| B. External Collaboration and Coordination | Established processes to collaborate and coordinate with agency partners and stakeholders on planning/visioning, target setting, programming, data sharing, and reporting. | To be successful in external collaboration activities in support of transportation performance management, agency staff must be successful at internal TPM activities; subcomponents of this component enable effective integration. |

| C. Data Management | Established processes to ensure data quality and accessibility, and to maximize efficiency of data acquisition and integration for TPM. | Similarly, staff must have the capability to manage data effectively for use in transportation performance management and integrate data into TPM processes. |

| D. Data Usability and Analysis | Existence of useful and valuable data sets and analysis capabilities, provided in usable, convenient forms to support TPM. | Staff must have access to usable data and have the skills necessary to analyze it; this component enables skill development. |

Regulatory Resources

This Guidebook is intended to assist agencies with implementing transportation performance management in a general sense, and not to provide guidance on compliance and fulfillment of Federal regulations. However, it is important to consider legislative requirements and regulations when using the Guidebook. In many cases, use of this Guidebook will bring an agency in alignment with Federal requirements; however, the following sources should be considered the authority on such requirements:

Federal Highway Administration

- Transportation Performance Management: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/tpm/links_fhwa.cfm

- Fact Sheets on Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/fastact/factsheets/

- Fact Sheets on Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21): https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/map21/factsheets/

- Resources on MAP-21 Rulemaking: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/tpm/rule.cfm

Federal Transit Administration

- Fact Sheets on FAST Act: https://www.transit.dot.gov/funding/grants/fta-program-fact-sheets-under-fast-act

- Resources on MAP-21: https://www.transit.dot.gov/regulations-and-guidance/legislation/map-21/map-21-program-fact-sheets